Noir Times 3 with Eddie G.

Film Noir the Dark Side of Cinema XVII 17th time is charmed! Kino’s long running noir series hits a winner: all three pictures are strict-definition noirs and two of them haven’t been easy to see on video. The set is also an Edward G. Robinson festival, charting three years when the grey-listed star was taking jobs where he could find them. Vice Squad is an amusingly ironic day in the life of a Los Angeles police captain; Black Tuesday a bleak and brutal gangster picture directed by Hugo Fregonese, and Nightmare is a remake by Maxwell Shane of his own Cornell Woolrich thriller from ten years before.

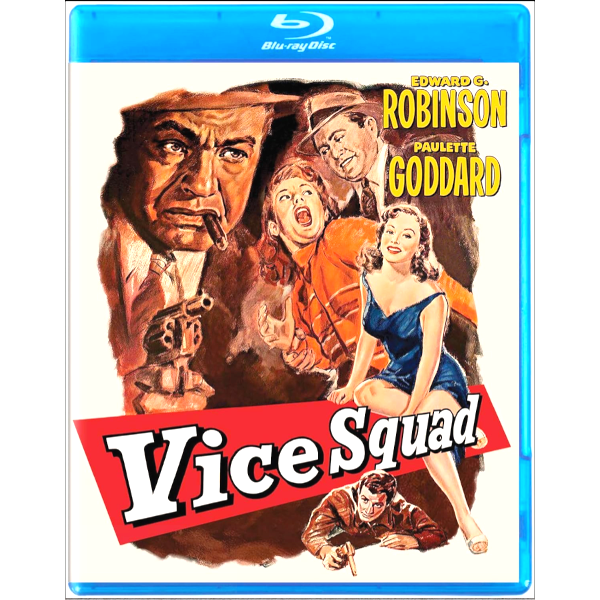

Film Noir the Dark Side of Cinema XVII

Blu-ray

Vice Squad, Black Tuesday, Nightmare

KL Studio Classics

1953-1956 / B&W / 1:85 widescreen & 1:37 Academy / 257 minutes / Street Date February 27, 2024 / available through Kino Lorber / 29.95

Starring: Edward G. Robinson, Paulette Goddard, Kevin McCarthy, Peter Graves, Jean Parker.

Directed by Arnold Laven, Hugo Fregonese, Maxwell Shane

You can’t go wrong with Edward G. Robinson, as even his lower-case thrillers from the 1950s all have something special to recommend them. The three here can all be classified as genuine films noir, as opposed to Kino’s practice of stretching the definition to almost any drama in B&W that isn’t a western or a musical. In a couple of cases, the noir aspect is just a matter of philosophical tone: a jaundiced view of police politics, a nihilistic streak opposed to the standard Law & Order status quo.

You can’t go wrong with Edward G. Robinson, as even his lower-case thrillers from the 1950s all have something special to recommend them. The three here can all be classified as genuine films noir, as opposed to Kino’s practice of stretching the definition to almost any drama in B&W that isn’t a western or a musical. In a couple of cases, the noir aspect is just a matter of philosophical tone: a jaundiced view of police politics, a nihilistic streak opposed to the standard Law & Order status quo.

All were released by United Artists and intended as first-run attractions. Each comes from a different production team, but all make good use of their star. And one sees Robinson trying on his old-time nasty gangster characterization, perhaps for the last time. All three appear to be Blu-ray debuts: Vice Squad, Black Tuesday and the generically-titled Nightmare.

Film Noir the Dark Side of Cinema XVII continues Kino’s series that bundles three separate discs in a stiff card box. The discrete keep cases make it easy to weed out the noir titles, when arranging discs on one’s shelf. We need to keep life’s important things in perspective.

Q

Q

Vice Squad

1953 / 1:37 Academy / 88 min. The Girl in Room 17

Starring: Edward G. Robinson, Paulette Goddard, Porter Hall, Adam Williams, Edward Binns, Barry Kelley, Jay Adler, K.T. Stevens Harlan Warde, Mary Ellen Kay, Lee Van Cleef, Lewis Martin, Murray Alper, Russ Conway, Percy Helton, Mickey Knox, .

Cinematography: Joseph F. Biroc

Art Director: Carroll Clark

Film Editor: Arthur A. Nadel

Original Music: Herschel Burke Gilbert

Written by Lawrence Roman from a book by Leslie T. White

Produced by Arthur Gardner, Jules V. Levy

Directed by Arnold Laven

Vice Squad is the sophomore feature effort from the prolific Levy-Gardner-Laven team, who began with the much smaller-scale serial killer tale Without Warning! United Artists green-lit them to produce two more noirs and then a quartet of low-budget sci-fi/horror pix. Vice Squad was lucky to find both Edward G. Robinson and Paulette Goddard looking for work. Ironically, Robinson had purchased the property for Vice Squad six years earlier, before the HUAC debacle crippled his career. Still, it’s a good role for him, playing a lawman instead of a crook.

The storyline interweaves a heist caper with a day-in-the-life portrait of a Los Angeles detectives’ bureau. Thieves Al Barkis and Pete Monty (Edward Binns & Lee Van Cleef) kill a policeman while stealing a car from a dealership. Reluctant witness Hartrampf (Porter Hall) doesn’t want to cooperate with Detective Captain ‘Barney’ Barnaby (Edward G. Robinson), who slyly arranges for both Hartrampf and his lawyer (Barry Kelly) to be inconvenienced and hassled all day long. A stoolie (Jay Adler) tips off the cops to the impending heist, while Barkis and Monty intimidate hoodlum Marty Kusalich (Adam Williams) to keep him from quitting.

Captain Barney appears on a TV show, manages departmental issues, and leans on his good friend Mona Ross (Paulette Goddard) for information. She happens to be an ‘escort madam’ with a special relationship with the detectives’ vice unit, but Barney has to throw her girls into jail cells before she cooperates, establishing a link between Kusalich and the murderous bank robbers. Barney’s squad sets a trap at a Beverly Hills bank…

The modest overachiever Vice Squad was filmed in 1953, in the same place and time commemorated in the 1997 exposé thriller L.A. Confidential. The ensemble character interactions are well choreographed, and the two action-suspense sequences are well done. Angelenos will easily recognize the Beverly Hills locations. The sullen Ed Binns is good as the gang leader and young Adam Williams excellent as the gunman who’d rather sit out the robbery at Mona’s place with his girlfriend. Edward G. Robinson carries the film beautifully, even if we mostly see him in the halls and offices of police headquarters.

What makes Vice Squad especially interesting now is its cavalier attitude toward Law and Order, with the kindly Captain Barnaby breaking rules that today would blow up into a career-ending newspaper scandal. He has a ‘winking’ relationship with Mona Ross, allowing her brothel to function in violation of the law. Her cooperation reminds us of the then-common practice for cops of all ranks to be in cahoots with the very vices they were supposed to suppress. This isn’t the squeaky clean Dragnet view of police work. The only thing missing is the race issue — non-Anglos don’t seem to exist in this vision of Los Angeles circa ’53.’

Even worse is Barney’s tormenting of Jack Hartrampf, through various illegal ruses that appear to be Standard Operating Procedure. A female undercover cop brushes up against Hartrampf, so he can be accused of molestation and held indefinitely. This running gag is treated as comedy relief, but it suggests that even well-intentioned cops will stretch the rules in the service of expediency.

Vice Squad concludes with a hostage taken and a showdown in an abandoned concrete building, located about a hundred yards North of the California Incline on Pacific Coast Highway in Santa Monica. Barney’s slick tricks down at headquarters save the day.

One of the sidebar stories sees a fake European count (John Verros) trying to get away with a crime called Marriage Bunco. Barney employs several paid city workers, including a language expert, to rescue a victim referred to as ‘a friend of City Hall.’ Remember, the L.A.P.D. is there to help, as long as you’re personally connected to the downtown Elite.

Edward G. Robinson makes all these shenanigans look like noble social work, and Paulette Goddard gives Mona Ross an appropriately flirtatious quality. Lee Van Cleef assays yet another slimy crook. The vivacious K.T. Stevens gets third billing — as Barney’s secretary she has little to do beyond convey information, but their scenes prove that Arnold Laven handles all kinds of scenes well.

Vice Squad was released in July of 1953, which makes its squarish Academy aspect ratio correct; the studios’ switch-over to widescreen would be happening for the entire next year. The B&W encoding looks and sounds great; what with all the nicely-integrated on-location exteriors, it’s obvious that the Levy-Gardner-Laven team was trying very hard for a quality product. The soundtrack is particularly clear, with Herschel Burke Gilbert’s exciting music score adding pep to many scenes.

All three films in this set are new remasters for HD.

Gary Gerani contributes audio commentaries to the first two titles in the set, offering solid background on the producers’ medium-budget effort and a scene-by scene rundown on locations and actor bios. We’re told that Herschel Burke Gilbert’s main theme became a popular needle-drop for afternoon TV movie presentations. Each disc commentary offers an Edward G. Robinson bio, but Gerani pitches his differently.

Black Tuesday

1954 / 1:85 widescreen / 80 min.

Starring: Edward G. Robinson, Jean Parker, Peter Graves, Milburn Stone, Warren Stevens, Sylvia Findley, Jack Kelly, Hal Baylor, James Bell, Vic Perrin, Russell Johnson, Lee Aaker, Arthur Batanides, Frank Ferguson, Thomas Browne Henry, Paul Maxey, Kenneth Patterson, Stafford Repp, William Schallert, Than Wyenn.

Cinematography: Stanley Cortez

Art Director: Hilyard M. Brown

Film Editor: Robert Golden

Original Music: Paul Dunlap

Screenplay and story by Sydney Boehm

Produced by Robert Goldstein

Directed by Hugo Fregonese

For Edward G. Robinson fans, the most exciting offering here will be this smartly-directed old-fashioned gangster ordeal. It is the first independent production of Robert Goldstein, who spent years in executive capacities for 20th Fox. The movie isn’t expensive, but it benefits from some proven talent starting with writer Sydney Boehm (The Big Heat, Violent Saturday) and cameraman Stanley Cortez (The Magnificent Ambersons, The Night of the Hunter). The film’s many small speaking roles were taken by actors clearly eager to work with Edward G. Robinson, who in this thriller is always in the middle of the action.

‘Black Tuesdays’ are when executions are carried out at the State Prison. Gangster Vincent Canelli (Robinson) and killer thief Peter Manning (Peter Graves) are due for electrocution, but Cannelli’s gang puts a daring plan into action. They force the cooperation of guard John Norris (James Bell) by kidnapping his daughter Ellen (Sylvia Findley). Hired trigger man Joey Stewart (Warren Stevens) takes the place of newspaper reporter Frank Carson (Jack Kelly) and springs Canelli, Manning and the other Death Row convicts using the gun that Norris has snuck into the execution chamber. Directly involved in the getaway is Canelli’s lover, Hatti Combest (Jean Parker).

The crooks escape, killing several guards. They take their hostages Carson, Father Slocum (Milburn Stone) and prison guard Lou Mehrtens (Hal Baylor) to a hideout in an old warehouse. But Manning is gravely wounded. The breakout was financed with the promise that Manning would lead the gang to $200,000 in stashed loot. Canelli is furious to learn that the money is sitting in a safety deposit box. Barely able to walk without fainting, Manning goes to the bank, with Hatti pretending to be his secretary. His picture is in all the papers. Will the ruse work?

At face value Black Tuesday is a generic, if brutal action gangster film that assembles standard characters in stock situations. With his career at low ebb, Edward G. Robinson agreed to exploit his popular Enrico Bandello – Johnny Rocco persona, essentially doing the same commercial backtrack James Cagney had done with White Heat and Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye. Eddie G. doesn’t snarl “Nyah, nyah!” but otherwise is his standard mob thug, in another tight spot.

Much of the fun in this small-scale movie is seeing favorite actors happy to work opposite the screen legend Robinson. Peter Graves is the hardened killer scheduled for a hot seat double-header; he builds and then wrecks a model bridge in his Death Row cell, a gag later re-used for Steve McQueen in The Getaway. ‘Forties favorite Jean Parker (soon to be seen on Blu-ray in Edgar Ulmer’s Bluebeard) may have been chosen because she’s 5’3″ inches tall, an inch shorter than Robinson. Parker is quite good as Canelli’s loyal moll. Secondary characters granted the most emphasis are James Bell’s traumatized guard, Warren Stevens’ professional hit man, and Milburn Stone’s priest. Russell Johnson (another thug) and Jack Kelly (handsome hostage) have less screen time. Vic Perrin plays a doctor low-key, while ex-Marine actor Hal Baylor gets the plum part of a prison guard who gets on Vincent Canelli’s bad side.

Almost every bit has a recognizable face, too: Arthur Batanides, Frank Ferguson, Kenneth Patterson, Thomas Browne Henry, Phillip Pine, William Schallert, Stafford Repp. Director Fregonese sees that each character makes the desired contribution to the whole.

Black Tuesday feels tightly wound, efficient. ‘Contained tension’ is the theme right from the start, when Canelli is introduced pacing in his cell like wild animal. Director Hugo Fregonese does excellent work with the film’s few exterior location scenes; outside a real prison, his moving camera creates a spatial logic as the mobsters wait to connect with Ellen Norris. Sydney Boehm’s script continuity also feels progressive, by letting several major scenes take place off-screen. We’re not shown the kidnapping of Ellen Norris, yet we remain cognizant of the danger she’s in. The only plot loophole that we question is the gang’s ‘replacing’ reporter Frank Carson with one of their own. Since Carson is a new hire, the assembed press corps doesn’t notice the swap. But how did the gang know that Carson’s editor wouldn’t go with the regular reporter? (Or did I miss a detail ‘covering’ this gap? It happens.)

We would argue that the show enters genuine noir territory via its overall bleakness, its avoidance of sentimental norms. There is no honor among thieves; the only value for these criminals is survival. Vincent Canelli invites several Death Row convicts to join in the escape, only to abandon them in the middle of the city. They become distractions to aid his own getaway. The priest’s protestations do nothing to halt Canelli’s plans to kill his hostages. The law is also powerless against the new ‘godless’ criminal logic: Frank Ferguson’s police inspector apologizes that he cannot bargain with Canelli, even if all the hostages will die.

The killings in Black Tuesday are cold calculations, the kind that would be condemned by the Kefauver Commission as contributing to juvenile delinquency. Vincent Canelli follows through on his threat to start killing hostages. The only reason he keeps Peter Manning alive is the $200,000 dollars Manning can access. Canelli appears devoted to his girlfriend Hatti, but even she can’t contain his rage when things go bad.

The business at the bank plays out in Beverly Hills, the same general location used for Vice Squad. Manning stops off at a movie theater to retrieve the safety deposit key. It’s hidden in what we would call a very un-secure place … what if that machine had been replaced, or was sent in for repair? We note that the theater is playing Fregonese’s current movie The Raid.

The dynamics of the final act are very well directed, considering that Hugo Fregonese hasn’t the resources to stage big action scenes. Hundreds and hundreds of rounds of ammo are fired in the warehouse standoff. We barely see the presumed army of cops outside, and Fregonese has to play the finale with various people being picked off, while the unstable Vincent Canelli edges closer to losing total self-control. Edward G. Robinson’s strong performance provides much of the last-minute blaze of glory. The characters may only be ‘types,’ but they’re very well sketched. Peter Graves’ final generous act provides a minimum of relief, even as it spares some of the hostages.

True, Black Tuesday is no masterpiece. But we like the way it plays out genre expectations with a touch of The New Nihilism, a refusal to sugarcoat everything. Even with a priest in the mix, the show really doesn’t compromise much with its premise.

Black Tuesday has not been an easy picture to see — we’ve been looking for it for what seems forever. Its appeal is obvious: how often do we get to see a ‘new’ movie starring Edward G. Robinson as a gangster? The excellent widescreen presentation has a nice noir look thanks to Fregonese’s direction and Stanley Cortez’s gritty visuals. The Death Row scene includes a close inspection of an actual Electric Chair, and the staging of the final standoff accentuates the light from high windows and floors littered with spent shells. The superior direction almost makes us forget that most of the show plays out in interiors easily mocked up on a studio lot. We don’t remember seeing any location shots of Edward G. Robinson, and one moving POV of a car in Beverly Hills feels like something grabbed on the sly. What we do remember is Vincent Canelli’s rage, Hatti’s attempts to control him, and Peter Manning’s bitter defiance.

The trailer included for Black Tuesday is a surviving textless item for foreign use. Screenwriter-author Gary Gerani offers a commentary for this title as well, giving the film a close read. He notes that the storyline falls into two halves, one in the prison and one in the hostage hideout. This show has fewer exterior locations to spot, but Gerani IDs the theater in the movie as being the Cameo at Santa Monica and Crescent Heights Blvds …. by the time we arrived in Los Angeles fifteen years later, it was long gone.

Nightmare

1956 / 1:85 widescreen / 89 min.

Starring: Edward G. Robinson, Kevin McCarthy, Connie Russell, Virginia Christine, Rhys Williams, Gage Clarke, Marian Carr, Barry Atwater, Meade ‘Lux’ Lewis, Billy May and His Orchestra, Virginia Lee.

Cinematography: Joseph H. Biroc

Art Director: Frank Sylos

Film Editor: George Gittens

Original Music: Herschel Burke Gilbert

Assistant Director: Robert H. Justman

Written by Maxwell Shane from the story by Cornell Woolrich

Produced by William H. Pine, William C. Thomas

Directed by Maxwell Shane

Of the three pictures in the set, Nightmare is the one most written up in essays about the noir style. It’s from a story by the noir author Cornell Woolrich. It’s also a ‘psychological’ thriller with an existential dilemma. A man is convinced that he’s killed someone, but all he can remember is a disconnected dream, a nightmare that doesn’t make any sense. That’s core noir territory, the kind of material that launches term papers and genre studies. Our daily lives are complicated enough, but do our personalities hide terrible anti-social drives?

What’s more, the film is an auteurist puzzle — it’s a direct remake of writer-director Maxwell Shane’s own Paramount picture Fear in the Night from only nine years earlier. The producers of that movie simply ‘did it again’ using the same script, writer and director.

Despite its star casting, Nightmare is an awkward attempt to bring Cornell Woolrich’s short story to life. The powerful opening segues from a dreamlike title sequence to a dream in medias res. Stan Grayson (Kevin McCarthy) recalls killing a man and hiding his body in a weird mirrored room — and almost nothing else. But when he wakes up in his rented room, he has a tell-tale key in his pocket and choke-marks on his neck. Convinced that he’s a murderer, Stan avoids his girlfriend Gina (singer Connie Russell) and tries to confess to his brother-in-law, detective Rene Bressard (Edward G. Robinson). Bressard makes light of Stan’s confusion until a picnic outing when he and Stan, Gina, and Rene’s wife Sue (Virginia Christine) flee a thunderstorm into a deserted mansion … which Stan senses is related to his dream. Sure enough, the bizarre mirrored room is waiting for him, upstairs.

The original Fear in the Night was writer Maxwell Shane’s first directing attempt; it runs 71 minutes and is mainly interesting as an early starring role for Star Trek fan favorite DeForest Kelly. Shane’s own remake tries to soften the gritty story for the 1956 mainstream. The locale has been changed to the more exciting New Orleans. The hero is now a clarinetist in (the real-life) orchestra of bandleader Billy May, and the girlfriend Gina is now a singer. Several songs have been added, but they don’t account for the story now playing out 18 minutes longer than the original.

Here’s a remake that retains the original’s every flaw.

The changes do nothing with a story in dire need of a radical rewrite — most every event and much of the dialogue is identical to the original 1947 film, a narrative packed with irrational coincidences and contrivances that work against our involvement. Revealing the cause of Stan’s loss of memory is no spoiler because the movie’s poster billboards the word HYPNOTISM in giant letters, simultaneously suggesting that Edward G. Robinson is the one hypnotized. Instead, we witness Kevin McCarthy stumbling about in sweaty psychological distress for the film’s entire 90 minutes. *

No Twilight Zone or One Step Beyond was ever as un-subtle with its ‘uncanny’ clues. Forget the terrible music cues that jog Stan’s memory, or the way he subconsciously directs his fellow picnicking party immediately to the scene of the crime. Forget that four adults steal their way into a house, start a fire in the fireplace, use the kitchen and snoop upstairs — yet easily explain themselves to a deputy looking for suspicious activity after a murder. And forget that no explanation whatsoever is offered for the construction of a special room that belongs in a hoary haunted house story, a room with mirrored doors, one of them leading to an escape route. A short story or even a radio show might be able to suspend disbelief for those things. They stand out as entirely bogus: Nightmare takes pains to offer a realistic surface — ordinary people in a real city.

Instead of looking for ways to make the story more plausible, the quickie remake just tacks on new material. Some of it is extraneous, like Stan Grayson’s dalliance with a barfly played by Marian Carr, fresh from her role as the “No” girl in Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly. Carr’s scene could be dropped with zero effect to the storyline … the producers surely just wanted to add a ‘babe’ to the story, with a kissing scene for the advertising.

Even United Artists must have been irritated by the film’s production deficiencies. Frankly put, most of Pine-Thomas’s pictures at Paramount took cheapskate shortcuts. Their 3-D efforts were filmed on tiny, fake sets, and their ‘epic’ adventure in Machu Picchu used location shots filmed in 16mm. The lighting for most of Nightmare is blah TV-caliber work, and the uninspiring New Orleans location shots just feature Kevin McCarthy walking through Bourbon Street. We’re surprised to see Edward G. Robinson on location for one street scene, as everything else outdoors uses terrible rear-projection. The musical recording session and nightclub performances are filmed flat as well. Band singer Connie Russell’s voice sounds good, but as actors neither she nor Billy May rise above amateur status. Couple that with the excellent McCarthy and Robinson struggling against a strained screenplay, and Nightmare requires a lot of patience.

Almost saving things is the mysterious opening. Excellent optical work by Howard Anderson launches the show with those dreamy main titles, and overlays Stan’s murder dream with ‘mind fog’ memory distortions. Otherwise, the show is something of a trial for all but genre analysts seeking out expressive themes — like the psychological significance of mirrors in the noir universe.

It’s not often that a film noir rubs us so entirely the wrong way — we give a pass to efforts almost as flawed. But Nightmare plays as if its makers were working on automatic pilot. Kevin McCarthy often looks as lost as his character, and it’s truly amusing to see the excellent Edward G. Robinson using the sheer strength of his personality, to impose credibility onto weak scenes.

This HD transfer looks even better than that for Black Tuesday, although the monotony of one high-key scene after the next gets old. In one setup Virginia Christine and Connie Russell take a nap, in an unnaturally bright room.

We wasted no time auditing Jason A. Ney’s audio commentary. He discusses everything relevant about Nighmare — the original source story, the first film version from 1947 and the changes made for the ’56 remake. Ney explains how the Pine-Thomas producing organization migrated from Paramount to United Artists. They pitched two literary adaptations to UA, but then substituted a pair of cheaply-made thrillers. Very inspiring is Mr. Ney’s account of Edward G. Robinson’s immigration story, and the disillusion Robinson suffered when the HUAC rewarded his enthusiastic patriotism with accusations of Communist subversion.

Reviewed by Glenn Erickson

Film Noir the Dark Side of Cinema XVII

Vice Squad, Black Tuesday, Nightmare

Blu-ray rates:

Movies: Vice Squad & Tuesday Very Good ++, Nightmare Good

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements:

Black Tuesday and Vice Squad commentaries by Gary Gerani

Nightmare audio commentary by Jason A. Ney

Textless trailer for Black Tuesday.

Deaf and Hearing-impaired Friendly? YES; Subtitles: English (feature only)

Packaging: One Blu-ray in Keep case

Reviewed: March 20, 2024

(7098noir)

* Kevin McCarthy’s greatest film Invasion of the Body Snatchers was filmed two years before but released around the same time as Nightmare. His character Dr. Miles Bennell is only in a sweaty panic in the last twenty minutes or so in that show. Stan Grayson is in a similar paranoid situation; one could edit scenes from the two together to create something totally irrational and absurd. First idea: replace Bennell’s nervous voiceovers about the Pod People crisis, with Stan Grayson’s worrisome voiceovers waxing poetic about his insane situation, trapped in a living nightmare.

Visit CineSavant’s Main Column Page

Glenn Erickson answers most reader mail: cinesavant@gmail.com

Text © Copyright 2024 Glenn Erickson

Ordered! Thanks.

does this bluray play in europe.?

I checked this specific disc for you. It will play only if your Blu-ray machine will play Region A discs. Many USA- domestic Kino discs are region-locked.

Slight mistakes while recounting a significant plot point in BLACK TUESDAY. Obviously a typo where you meant to state that Edward G. Robinson’s character Canelli is furious to find out that Manning , played by Peter Graves, hid the stolen money in a bank’s safety deposit box. You say Manning is furious to learn it, which makes no sense since he is the one who hid it there! Further, you say that Jean Parker accompanies Manning to the bank to retrieve the loot while posing as his wife. In reality, Manning refers to her to the bank clerk as his “secretary.”

Thanks Arthur … much appreciated !