The Prisoner

Alec Guinness transfers an acting challenge from the stage to the screen, in this account of a Cardinal forced to knuckle under to a Communist regime — instead of extracting a confession with torture, Jack Hawkins’ Inquisitor uses psychology to find his prisoner’s weakness. The picture is uneven but its key performances are choice, with a special assist from Wilfrid Lawson as a jailer.

The Prisoner

Blu-ray

Arrow Academy

1955 / B&W / 1:85 widescreen / 95 min. / Street Date March 12, 2019 / 39.95

Starring: Alec Guinness, Jack Hawkins, Wilfrid Lawson, Kenneth Griffith, Jeanette Sterke, Ronald Lewis, Raymond Huntley, Percy Herbert.

Cinematography: Reginald Wyer

Film Editor: Frederick Wilson

Original Music: Benjamin Frankel

Written by Bridget Boland from her play

Produced by Vivian Cox

Directed by Peter Glenville

Is this an anti-Communist piece, or simply a story about human convictions and human weakness? Believe it or not, some interpreted it as anti-Catholic in 1955. European film festivals may have turned it down to stay clear of political or spiritual controversy.

Movie history abounds with high-toned pictures about the human spirit in extremis, and of men of the cloth put in situations where they must endure the sufferings of Christ… stories of this sort can be pretentious or inspirational, depending on the talent involved. When topical politics come into play there’s a big risk of attracting inflammatory charges of propaganda — the Cold War years saw several highly-confused pictures that mixed politics and religion — Red Planet Mars and The 27th Day, to name two. But The Prisoner is about real political oppression by regimes that would not tolerate the competition of churchmen for their citizens’ hearts and minds.

Bridget Boland and Peter Glenville’s The Prisoner comes straight from the stage with its original star Alec Guinness intact. More than one critic on this disc notes that the actor’s experience with the play may have led to his converting to Catholicism two years later.

The show is basically a two-character battle, and onstage likely played out in just a couple of sets. As with other ‘meaningful’ stories, a specific country is not named. But dialogue makes it clear that the country is an Eastern Bloc satellite. And it was no secret that the play was inspired by the show trial and imprisonment of a Hungarian Cardinal in 1949.

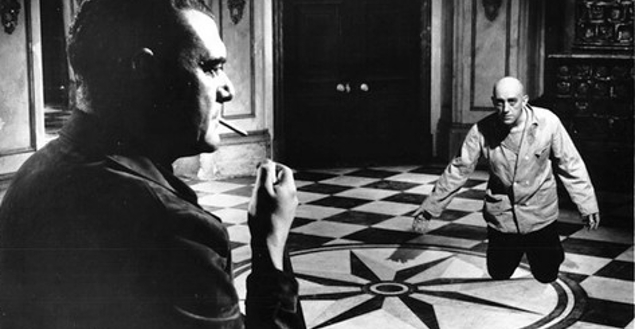

The characters are not given names either. After a morning Mass, The Cardinal (Alec Guinness) is arrested for treason, put in prison and questioned by The Interrogator (Jack Hawkins). The churchman and the former doctor were once comrades in the resistance against the Nazis. That was just a few years before, but now the new totalitarian government needs to discredit the church, which is perceived as the enemy of the new order. Thus The Interrogator’s task is to get The Cardinal to confess to non-existent treason. As The Cardinal successfully resisted Nazi torture, The Interrogator uses psychological methods to attain his goal. To the discomfort of The General (Raymond Huntley), demonstrations and resistance must be put down; newspapers demanding to know why The Cardinal is being held without trial are silenced. The prisoner and his interrogator mostly talk in tangents about the impasse between them, and examine their opposing roles in a strange charade. The Cardinal mocks the flimsy evidence of treason presented against him. But The Interrogator eventually finds several chinks in The Cardinal’s armor — his past with his mother and petty secrets from his youth, and goes to work using The Cardinal’s pride and humility as weapons against him.

Theater man Peter Glenville acted in a handful of films but made his mark directing a some high-profile pictures, especially 1964’s Beckett. This is his first film as director and he acquits himself well. The ‘opening up’ of the play is less successful. Some exteriors were filmed in Belgium to represent the harsh streets of an Iron Curtain city. A nicely-staged sequence during a mass begins the film with a five-minute sequence without dialogue, as The Cardinal is delivered a note that he will be arrested, right in the middle of the ceremony.

The only really deleterious scenes involve the relationship of a prison clerk (Ronald Lewis of Mr. Sardonicus) with a married woman (Jeanette Sterke) whose husband has left the country and cannot return — their story is dropped without comment. We also witness the shooting of a boy caught chalking freedom slogans on a wall. None of this particularly subtle, or emotionally effective.

In contrast to the rather deep mind games played during the interrogation sessions, author Boland gives us fairly numbing exchanges between Hawkins’ Inquisitor and Raymond Huntley’s humorless Party functionary, fretting about potential uprisings of ‘the people’ and putting pressure on a quick confession from the cagey Cardinal. One of The Inquisitor’s ploys is to bring The Cardinal’s mother to the prison, unconscious under a white sheet on a gurney. When The Cardinal admits that he never loved his mother the way a son should, The Inquisitor has finally found a weakness he can exploit. Has The Inquisitor been reading Kafka?

Governments today can easily fabricate ‘evidence’ of treason for whatever purpose might be needed, but back in the postwar era, things weren’t so sophisticated. The Inquisitor has faked ‘insurrection’ maps glued together from clippings of The Cardinal’s handwriting. Using a tape recorder and a record cutter, an assistant also cuts and pastes bits of audio recordings of the interrogation sessions, to make it sound as if The Cardinal is admitting crimes against the state. But The State needs The Cardinal to confess willingly, in a public trial. The Interrogator must somehow break his prisoner down entirely. It’s not brainwashing, but a defeat of the personal will.

At this point in his career Alec Guinness was known in film mainly as a chameleon comedy actor, despite performing in several dramas. Without a special wig and with dark makeup around his eyes, he almost looks like an Egyptian Pharaoh. His dead-eye stare also resembles his later role as the secret policeman brother of Doctor Zhivago. Much of his performance seems familiar until The Cardinal begins to crack, at which point the play and Guinness go in an unexpected direction, avoiding hysterical theatrics. At one point we think the Cardinal may choose being executed, just to relieve him of the pressure of his new guilt for being a failed cleric.

Jack Hawkins’ solid support helps things considerably — he’s the only actor whose skill disguises the expository lapses in the play, when things are spelled out too clearly. Of the other actors, only two make a strong impression. Kenneth Griffith is quite good as The Secretary, The Inquisitor’s general flunky and manipulator of audio recording machines. Griffith doesn’t put any spin on this role, to make The Secretary seem a degenerate, etc. — he’s just doing a job that must be done. Horror fans will immediately recognize Griffith from his great part in the squeamish shock classic Circus of Horrors, where he plays a less in-control flunky, aiding and abetting dastardly crimes.

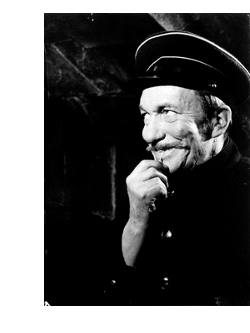

Unlike humorless pictures about similar terrible persecutions (John Frankenheimer’s The Fixer comes to mind), The Prisoner adds a kind of comic relief to the proceedings, without throwing the overall tone out of whack. Third-billed Wilfrid Lawson may be known to American audiences as Wendy Hiller’s ‘undeserving poor’ father in the original 1938 Pygmalion. Lawson also shows up to good effect in Tom Jones, The Wrong Box, Expresso Bongo, Hell Drivers and The Long Voyage Home. Here he has a substantial role as the prisoner’s Jailer. Apparently even prison turnkeys in Communist countries are allowed to have eccentric personalities. During the booking process The jailer delights in criticizing The Cardinal, but is intrigued when his charge gets down on his hands and knees to scrub his cell spotless. By the end The Jailer is thoroughly on The Cardinal’s side, and even makes this dissenting opinion known to others. The movie needs this kind of tone shift, and Lawson performs it well.

Less successful is the ‘deep’ resolution wherein prisoner and inquisitor figuratively change places. The filmmakers keep The Cardinal’s future in a cloud of ambiguity, but Hawkins’ Inquisitor comes down with a too-easy-to-predict Judas guilt complex.

Arrow Academy’s Blu-ray of The Prisoner is a fine HD transfer of the film, handled by its American distributor Columbia (Sony). Four minutes were apparently cut from the film for its U.S. release, but no mention is made of what these might have been — was something deemed offensive to us sensitive Americanos, or did someone just want to hurry up the film’s pace?

The image looks quite good, with just a tiny hint of a scratch here and there; a few cut points jump at the splice, which is a little unexpected. Otherwise we have no complaints; Alec Guinness fans will not feel cheated. Benjamin Frankel’s music score is quite good, drumming up feelings of conflict and importance without resorting to clichés.

The presentation comes with worthwhile critical extras. Neil Sinyard’s 20-minute video interview dispenses interesting information about the film and its reception. So do Philip Kemp’s partial commentary (four scenes) and the insert pamphlet’s essay by Mark Cunliffe. I took in all three and can say that I didn’t find much content overlap between them — each has its own angle of approach.

Reviewed by Glenn Erickson

The Prisoner

Blu-ray rates:

Movie: Very Good

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Interrogating Guinness, a video appreciation by Neil Sinyard; Select scene commentary by Philip Kemp; Illustrated collector’s booklet with an essay by Mark Cunliffe.

Deaf and Hearing-impaired Friendly? YES; Subtitles: English (feature only)

Packaging: One Blu-ray in Keep case

Reviewed: April 17, 2019

(5987pris)

Visit CineSavant’s Main Column Page

Glenn Erickson answers most reader mail: cinesavant@gmail.com

Text © Copyright 2019 Glenn Erickson