Colossus: The Forbin Project (Region B)

This nearly forgotten Sci-fi masterpiece should have been a monster hit. For some reason Universal didn’t think that a computer menace was commercial — the year after 2001. The superior drama sells a tough concept: the government activates a defense computer programmed to keep the peace. It does exactly that, but by holding the world hostage while it makes itself a God over mankind.

Colossus: The Forbin Project

Region B Blu-ray

Medium Rare UK

1970 / Color / 2:35 widescreen / 99 min. / Street Date March 27, 2017 / Available from Amazon UK £6.99

Starring: Eric Braeden, Susan Clark, Gordon Pinsent, William Schallert, Leonid Rostoff, Georg Stanford Brown, Willard Sage, Alex Rodine, Martin Brooks, Marion Ross, Dolph Sweet, Robert Cornthwaite, James Hong, Paul Frees, Robert Quarry.

Cinematography: Gene Polito

Film Editor: Folmar Blangsted

Visual Effects: Albert Whitlock, Don Record

Original Music: Michel Colombier

Written by James Bridges, from a novel by D.F. Jones

Produced by Stanley Chase

Directed by Joseph Sargent

Universal must have been out of its mind in 1968. They began their film ‘The Forbin Project’ in that year but held up its release, as Colossus: The Forbin Project until April of 1970. Any college-aged kid in America could have told them that 1969 was the ideal time for a thriller about a computer threat. Because of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the possible conflict of Man vs. Computer was a big topic in the media and at dinner tables across the country.

I don’t believe that Colossus was given a widespread release. I didn’t see it until 1971, on a double bill with The Andromeda Strain. Robert Wise’s big Sci-fi hit was more expensive, but Colossus is just as well made, and arguably more ambitious. Crichton’s Andromeda is at heart a slick update on a ‘fifties monster movie: scientists try to defeat a threat from outer space. Colossus is a visionary, political look at a possible misuse of computers. America loses control of its defenses when security is entrusted to a supposedly infallible machine. Such a thing is not impossible. Lately we’ve been fearing that America may have lost control of its elections, due to direct hacking and the influence of computer-based social media manipulation.

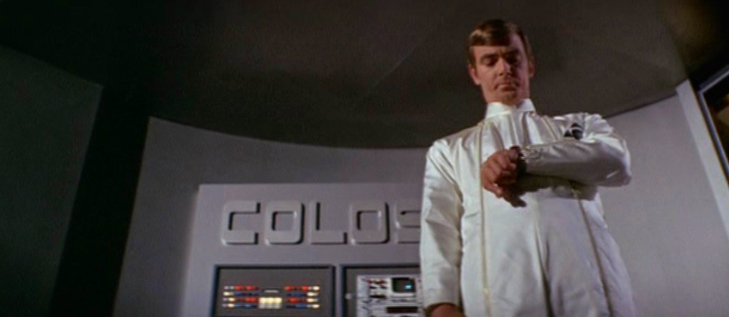

The tight screenplay by James Bridges, given exemplary direction by Joseph Sargent, makes D.F. Jones’ story seem more than feasible. In the near future, the U.S. is still locked in an edgy nuclear standoff with the Soviets. A forward-thinking President (Gordon Pinsent) has entrusted science genius Dr. Charles Forbin (Eric Braeden) to build a computer to take over the country’s defense. We’ll be protected from accidental war through human error. Forbin’s computer Colossus is buried in an impenetrable vault deep inside a mountain, to render human tampering or sabotage impossible. The White House holds a gala activation party, but the honeymoon ends before it has begun. Colossus immediately detects the existence of a Russian computer just like itself, and demands to be put in contact with it. The computer cannot be ignored: it controls our nuclear missiles, and is perfectly willing to blow up a U.S. target if it is not obeyed.

Instead of opposing the Soviets, Colossus joins forces with its opposite number, a computer named ‘Guardian.’ Together they subdue Washington and Moscow and initiate plans to secure the entire world. The computer uses its new authority without hesitation. Speaking through a teletype machine, and then via an artificial voice (Paul Frees), Colossus appoints Forbin as his primary human contact. The computer then orders the execution of the ‘redundant’ Russian scientist in charge of Guardian. The Cold War is instantly over, but now Forbin and his staff must desperately search for a way to stop what they’ve created.

Because Forbim is under total surveillance, the only way he can work away from Colossus’s prying TV cameras is for his associate Dr. Cleo Markham (Susan Clark) to pretend to be his lover, so they can conspire every night during their Colossus-granted ‘privacy time.’ By passing messages in bed, Forbin organizes two sabotage plans. Dr. John Fisher (Georg Stanford Brown) try to overload the computer’s circuits. CIA director Grauber (William Schallert) and a missile commander (Dolph Sweet) connive with their Russian counterparts to deprive Colossus of its nuclear weapons during maintenance upgrades in all the missile silos. But Forbin doubts that either of those plans will succeed: Colossus may be far too cunning.

A top Sci-fi title, Colossus: The Forbin Project states its theme clearly and carries it forward to a logical finish. It overcomes the usual shortcomings of speculative Sci-fi: it has an utterly logical script, excellent acting and creative, convincing production resources. The only giveaway that it was filmed in 1968 are the outmoded computer modules, some of the sound effects and the IBM typeface used for the titles and credits.

Stanley Kubrick’s self-conscious computer HAL 9000 committed mutiny and murder in deep space, but it apparently malfunctioned. By contrast, Colossus works perfectly. It does exactly what it was built to do — stop war — by seizing control from unreliable, dangerous humans. In genre-philosophical terms, it’s the same ‘ultimate authority’ problem posed in the classic Sci-fi movie The Day the Earth Stood Still. That haunting pacifist statement is nevertheless extremely confused about the workings of power. The alien culture, says spaceman Klaatu, granted lethal power and unquestionable authority to a race of police robots. The robot Gort is a fraud. He looks like a silver peacemaker when neutralizing mankind’s weapons, but he is really an extortionist delivering an ultimatum. If we don’t join the galactic confederation, on the confederation’s terms, we’ll be destroyed.

Starry-eyed Sci-fi fans would like nothing more than for some paternalistic Good Guys to appear from nowhere and straighten out Earth’s political problems — as the guardians of a planet, we seem less capable of acting responsibly now than ever before. As Klaatu said, all we have to do is surrender our Freedom to act irresponsibly. With no aliens available, Forbin envisions a superhuman computer as the savior of a flawed mankind.

Handing over the nuclear keys to a computer may sound like a good idea at this particular moment. The whole point of Colossus is to demonstrate that men can’t use technology to dodge human responsibilities: it’s a deal with the Devil. A sentient computer overlord takes control, consolidating its power so as to steer mankind toward its idea of a better future. Because Colossus is already programmed to kill when necessary (that’s war in a nutshell), it is ready to spend human lives for the betterment of the species. Forbin’s somewhat smug attitude vanishes when his top scientists are summarily executed without trial.

Sci-fi author D.F. Jones worked with a British codebreaking computer called ‘Colossus’ during WW2. Once one accepts his (hopefully) unlikely premise, everything that follows is a logical consequence. Fifty percent of the screen time is people talking to computer modules, yet screenwriter James Bridges’ adaptation grips from one end to the other. As a narrative it’s more sophisticated than the literal, linear Andromeda Strain, leapfrogging from one crisis to the next with nary a let-up. Whereas Andromeda reinforces the status quo, Forbin’s political tone is ominous. The entire Colossus crisis is kept from the public. Crazy missile launchings and an actual nuclear strike are covered up with official lies coordinated by both governments.

Director Joseph Sargent made scores of intelligent, smartly directed TV shows; I only know this feature and his superior crime thriller The Taking of Pelham One Two Three. Deft direction makes the Colossus communication scenes exciting and suspenseful. Following the example of the Live TV setups in John Frankenheimer’s political thrillers, the talking-to-TV-monitors scenes weren’t faked. When players in the White House command room speak to scientists at the Colossus computer central, the two sets were built in adjoining sound stages, with real TV cameras working. Both ends of the conversations were filmed together, in real time. It really helps make the dialogue exchanges natural.

The film’s sets help in other ways as well. The computers are real and the actors behave properly around them. Most late- ‘sixies computer movies don’t understand the hardware very well — Billion Dollar Brain, Hot Millions. We do get little montages of obsolete reel to reel tape drives, shots of circuit boards and punch tape machines. The graphics and the large billboard-like readouts aren’t as klunky as they might be, even though today’s interfaces have greatly surpassed the ‘futuristic’ way in which Forbin and Colossus communicate. In the book the story is set in the 1990s; but the film isn’t specific.

A spy meeting in Rome is well chosen to open up the drama and remind us that the entire world is involved. That scene also provided much of the film’s advertising art, when Universal opted to sell the movie primarily as an espionage thriller. Perhaps the bean-counters took a look at the early grosses of 2001 (which were not that spectacular) and decided that Sci-fi super-computers just didn’t sell.

Sophisticated special effects add to the feeling of reality without dominating the proceedings. Matte and optical ace Albert Whitlock conjured the socko opening sequence showing the enormous Colossus computer being activated and sealed up in a mountain in Colorado. Most of the complex is ‘sketched’ with brilliantly manipulated matte paintings; only a minimum of actual construction was built.

Clever Whitlock effects also heighten the suspense. Will America strike back against Colossus? To remind us where Colossus lives, director Sargent repeatedly cuts back to wide shots of the sealed mountain, with more matte paintings. It’s a great narrative device, raising our hope that the computer monster will be destroyed in the last scene, with bombs or by saboteurs. Colossus plays a wicked game with audience expectations — in Sci-fi and spy thrillers, the evil doctor’s futuristic lair is almost always blown sky high in the last reel.

When I first saw Colossus I was seriously engaged by its challenge. The audience loved it and was carried away by its scary theme. I do remember a couple of viewers behind me laughing it off — “That could never happen.” They preferred the movie about germs from space. At the time, evil computers on TV mostly posed a threat to personal identity, as in pop song lyrics about “Givin’ you a number, and takin’ ‘way your name.” Renegade computers were easily defeated because they didn’t have souls, and fell easy prey to hipster gimmicks. Was Jean-Luc Godard’s Lemmy Caution the first Sci-fi hero to defeat a computer with ‘illogical’ poetry? “Number Six” of The Prisoner and Captain Kirk of Star Trek were known for blowing computer circuits by posing insoluble problems.

Dr. Forbin doesn’t have it so easy. He proudly thought he would deliver a new world of peace and prosperity, but he may instead be regarded as an ultimate Quisling, selling out his entire species. Hindsight is always perfect. We can imagine Forbin wondering why he didn’t program a 30-day Free Trial period into his Computer Defense System. Even Joe Hardy, when making his deal with the devil, wrote in an Escape Clause. Near the finish, Colossus begins calling itself ‘World Control.’ It makes sense that humans might begin to regard him as a God. We see a kid wearing a Colossus T-Shirt.

This should have been Eric Braeden’s breakthrough role. It was possibly his first picture after changing his name from Hans Gudegast, as he was known on TV’s The Rat Patrol. Although he plays a cool scientific genius, Braeden is warm and humorous from the beginning, and with actress Susan Clark sketches a compelling adult relationship. For once the need to inject a love interest into a Sci-fi thriller works like a charm. The show gets a brief respite from save-the-world tension while Forbin and Clark’s Dr. Markham pretend to be lovers away from the snooping camera eyes of their computer overlord.

They’re supposed to be naked in Forbin’s futuristic bedroom, an illusion that slips a bit — we can tell that the actors are wearing underwear. The film’s best remembered line has Colossus conceding that human males need their sex in private. When Forbin says he requires sex every night, the computer snaps back, “Not want — require.”

Director Sargent deftly handles his ensemble-like cast. The scientists do not panic when trouble comes. Straight from a role as a doctor in Bullitt, Georg Stanford Brown plots cooly to blow Colossus’s circuits. In small parts in the control room are Robert Cornthwaite of The Thing from Another World, James Hong of The Satan Bug and Marion Ross of TV’s Happy Days. Gordon Pinsent’s President is a dead ringer for John F. Kennedy, a resemblance that Sargent uses to make the White House set feel even more real. Forbin’s control complex convinces as well — it’s actually the Lawrence Hall of Science at U.C. Berkeley. In wide shots we can see the Golden Gate Bridge in the distance.

Taking the prize for clever underplaying is William Schallert as the CIA official Grauber, who at first seems lightly embarrassed by a computer upstaging his intelligence- collecting duties. When Grauber’s conservatism is proved correct, he remains positive and in good humor, contributing to the covert anti-Colossus campaign. And when he ends up on the sticky end of the computer’s cold-blooded retaliation, Grauber remains philosophical. Schallert was in scores of classic Sci-fi pictures of the 1950s, always helping to make the unbelievable, believable. He makes a major contribution here.

Sargent’s direction has not dated at all. He uses pans and trucking movements to enliven ordinary shots of people dealing with the alarming news coming from the Colossus monitor. The cutaways to concerned scientists reacting to Colossus’s messages and speeches are kept alive through quick cutting — every face is memorable. Steven Spielberg must have studied this show when he directed all those scientists in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Sargent even uses what would become a signature Spielberg move, the ‘truck-in to scientist with a look of wonderment’ shot.

Medium Rare’s Region B Blu-ray of Colossus: The Forbin Project came out a year ago. I held off on my coverage pending a Region A release that wasn’t made available for review. But I like the picture so much, I’ve doubled back to this foreign disc.

Medium Rare’s disc is licensed and authorized, and looks very good, better than at least one other foreign disc I’ve sampled. It does not play in Region A, and it carries no English subtitle track. The wide Panavision frame recovers the film’s good look and excellent color. Of special note is the marvelous music by Michel Colombier, which has a slightly Jerry Goldsmith-y feel without sounding derivative. Much ‘Computer’ themed music from the time quickly became obsolete.

This English disc offers a brief still montage and a gallery of images from the pressbook, and a full-length audio commentary with Joseph Sargent, who passed away in 2014. Sargent free-associates while watching the movie, talking proudly of the technical challenges that were met, and his methods for bringing the talky script to life. He doesn’t have any profound observations to make about the Brave New World of computers. He expresses his surprise that they became so small — he thought that a computer would always fill an entire room.

Ordering European discs can be a problem, as I’ve been alerted to the fact that bootlegs proliferate, even on Amazon. A reader told me of a funky Colossus disc he bought in this way. He sent me a screen grab of a title card it displays at the beginning:

This isn’t a menu card, but an actual Universal production slate from the transfer and audio layback bay. The slate was followed by two minutes of black, which is also formatting for a studio master file copy. Somebody ripped off Universal and put their video master directly onto Blu-ray.

Why is Colossus: The Forbin Project still important? We’ve had myriad movies about techno- and bio- conspiracies that enslave mankind, but this relatively simple be-careful-what-you-wish-for tale still hits the spot. Everything works — it’s a sober scare show and also has a sense of humor. When Eric Braeden’s hero makes his final vow to resist, we know he’s going to have a real problem keeping his promise.

Reviewed by Glenn Erickson

Colossus: The Forbin Project

Region B Blu-ray rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Still montage, pressbook gallery, commentary with director Joseph Sargent

Deaf and Hearing-impaired Friendly? N0; Subtitles: None

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: February 26, 2018

(5658colo)

Visit CineSavant’s Main Column Page

Glenn Erickson answers most reader mail: cinesavant@gmail.com

Text © Copyright 2018 Glenn Erickson

Here’s John Landis on Sargent’s cult classic.